Our world is a symphony of sounds – from the delicate whisper of leaves to the complex melodies of a favorite song, from the urgency of a car horn to the nuanced intonations of human speech. But how do our ears, these marvels of biological engineering, manage to dissect this cacophony into meaningful information? At the heart of this incredible feat lies a tiny, often overlooked structure deep within your inner ear: the basilar membrane. Understanding its intricate anatomy and structure is not just an academic exercise; it's key to unlocking the secrets of hearing itself, and crucial for innovations that restore sound to those who have lost it.

At a Glance: Your Inner Ear's Sound Analyst

- Location: Tucked inside the fluid-filled cochlea of your inner ear.

- Purpose: The primary site for analyzing sound frequencies and converting sound vibrations into electrical signals your brain can understand.

- Key Feature: It varies in width and stiffness along its length – narrow and stiff at one end, wide and flexible at the other.

- Mechanism: This structural gradient allows different parts of the membrane to vibrate in response to different sound frequencies, creating a "place code."

- Vital Role: Essential for distinguishing between pitches, understanding speech, and appreciating music.

- Vulnerability: Susceptible to damage from loud noise, certain medications, and aging, leading to hearing loss.

The Cochlea's Unsung Hero: Why the Basilar Membrane Matters So Much

Imagine trying to differentiate between hundreds of instruments playing simultaneously, or picking out a single voice in a crowded room. Your brain does this effortlessly, thanks in large part to the basilar membrane. This flexible, yet remarkably precise, strip of tissue acts as the cochlea's internal sound analyzer, taking incoming sound vibrations and spreading them out like a rainbow of frequencies. Without its unique properties, the rich tapestry of sound would be a monotonous hum, and the nuanced world of human communication would be profoundly altered.

It's the unsung hero, the silent workhorse that enables us to enjoy everything from a gentle purr to a roaring thunderclap. Its sophisticated design underpins nearly every aspect of our auditory experience, transforming simple pressure waves into the complex data that eventually forms our perception of sound.

Peeling Back the Layers: A Closer Look at Basilar Membrane Anatomy

To truly appreciate the basilar membrane's function, we first need to understand its physical blueprint. It's not just a simple sheet; it’s a meticulously constructed component, perfectly integrated into the complex architecture of the cochlea.

Location and Orientation: Bridging the Inner Ear's Channels

Deep within the snail-shaped cochlea, the basilar membrane acts as a crucial internal partition. It stretches like a taut ribbon from the tympanic lip of the osseous spiral lamina – a bony shelf projecting from the central pillar of the cochlea – all the way to the basal crest, a ridge on the outer wall of the cochlea. This placement is not arbitrary; it's precisely positioned to form the floor of the scala media (also known as the cochlear duct) and simultaneously complete the roof of the scala tympani. This strategic separation is vital, as it allows for the distinct fluid dynamics necessary for sound transduction. It creates a critical interface where sound energy can be effectively transferred and processed.

The Two Distinct Zones: Zona Arcuata and Zona Pectinata

The basilar membrane isn't uniformly constructed; it comprises two principal parts, each with specific structural roles:

- Zona Arcuata (Inner Part): This thinner, more delicate section lies closer to the central axis of the cochlea, towards the osseous spiral lamina. Its primary role is to provide foundational support for the spiral organ of Corti, the true sensory epicenter of hearing. Think of it as the sturdy, yet flexible, foundation upon which the hair cells – the actual sound receptors – are carefully arranged. Its arched shape contributes to its structural integrity.

- Zona Pectinata (Outer Part): Broader and thicker than its inner counterpart, the zona pectinata extends towards the outer wall of the cochlea. Its name, derived from "pecten" (comb), hints at its striated appearance, reflecting the arrangement of its fibers. This section is more pliable and less directly involved in supporting the organ of Corti, but its unique mechanical properties are paramount for the membrane's overall vibratory response.

Hidden Details: The Vas Spirale and Supporting Tissues

Beneath the basilar membrane's surface, particularly on the side facing the scala tympani, lies a layer of vascular connective tissue. This tissue provides essential nourishment and structural integrity. Embedded within this layer, directly below Corti’s tunnel (a space within the organ of Corti), is a distinct blood vessel known as the vas spirale. This vessel ensures a vital blood supply to the surrounding structures, highlighting the metabolic demands of this highly active sensory apparatus. These supporting elements, though often overlooked, are indispensable for the long-term health and function of the entire auditory system. To truly grasp its intricate design, explore the basilar membrane schematic here.

The Engineering Marvel: How Structure Dictates Function

What makes the basilar membrane so extraordinary isn't just its presence, but its incredibly clever design. This design isn't uniform; it's a precisely engineered gradient that directly dictates how it responds to different sound frequencies.

The Gradient: Width, Stiffness, and Flexibility Along Its Length

Imagine a series of piano strings, each tuned to a different note. The basilar membrane operates on a similar principle, but its "tuning" is inherent in its physical structure. This is perhaps its most crucial characteristic:

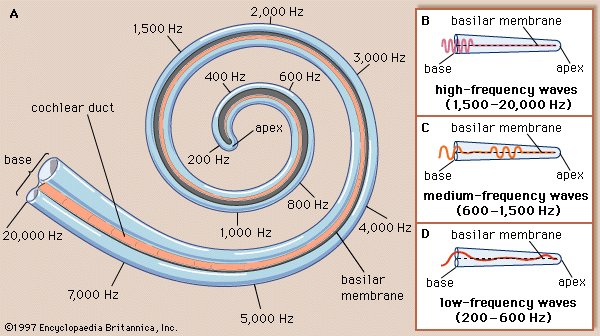

- At the Base (near the oval window): Close to where sound waves first enter the cochlea, the basilar membrane is narrower and significantly stiffer. Think of a short, thick string – it vibrates at a higher frequency. This region is exquisitely tuned to respond to high-frequency sounds.

- At the Apex (near the helicotrema): As the membrane winds towards the inner tip of the cochlea (the helicotrema), it gradually becomes wider and much more flexible. Picture a long, thin string – it vibrates at a lower frequency. This apical region is specialized for detecting low-frequency sounds.

This continuous, gradual change in both width and stiffness along its approximately 35 mm length creates a precise and predictable mechanical gradient. Each segment along the membrane has a unique natural resonant frequency, allowing it to act like a finely tuned filter bank.

From Sound Wave to Mechanical Vibration: The Pressure Dance

So, how does this structural marvel translate sound into something meaningful? It all begins with pressure differences. Sound waves entering the ear cause the eardrum to vibrate, which in turn moves the ossicles (tiny bones) in the middle ear. The last ossicle, the stapes, pushes on the oval window, setting the fluid within the cochlea into motion.

This fluid movement creates pressure differences between the scala media and the scala tympani, on either side of the basilar membrane. These oscillating pressure differences cause the basilar membrane to vibrate. Crucially, due to its varying stiffness and width, different sound frequencies cause maximum vibration at different locations along the membrane.

- A high-frequency sound will cause the narrow, stiff base to vibrate most vigorously.

- A low-frequency sound will cause the wider, more flexible apex to vibrate most.

- Complex sounds, containing multiple frequencies, will create a pattern of vibrations across different regions of the membrane simultaneously.

This spatially organized vibration pattern is the foundation of our ability to discriminate between different pitches.

Decoding Sound: The Basilar Membrane's Role in Frequency Analysis

The mechanical vibration of the basilar membrane is just the first step. The true magic happens when these physical movements are converted into electrical signals that the brain can interpret as sound.

The "Place Code" or "Tonotopic Map" Explained

The phenomenon described above – where specific frequencies cause maximum displacement at specific locations along the basilar membrane – is known as the "place code" or "tonotopic map." It's like having a map of sound frequencies laid out physically along the membrane. High frequencies are "mapped" to the base, and low frequencies to the apex.

This tonotopic organization is profoundly important because it's not just a feature of the basilar membrane; it's preserved throughout the entire auditory pathway. From the cochlea, this frequency map is maintained as signals travel through the auditory nerve, the brainstem, the thalamus, and eventually to the auditory cortex in the brain. This consistent mapping allows the brain to interpret the location of activity along the basilar membrane as a specific pitch, enabling the detailed analysis of complex sounds like speech and music.

Hair Cells: The Transducers of Sound

Sitting atop the basilar membrane, within the organ of Corti, are thousands of delicate sensory cells known as hair cells. These cells are the true transducers of sound, converting mechanical vibrations into electrical signals. Each hair cell has tiny hair-like projections called stereocilia that are embedded in or closely associated with another membrane called the tectorial membrane.

When the basilar membrane vibrates in response to sound, it moves relative to the tectorial membrane. This shearing motion causes the stereocilia of the hair cells to bend. This bending is the critical event: it opens ion channels in the hair cells, leading to a change in their electrical potential.

Sending the Signal: From Mechanical to Electrical

The change in electrical potential within the hair cells triggers the release of neurotransmitters. These neurotransmitters, in turn, excite the dendrites of auditory nerve fibers that are synapsed with the hair cells. This excitation generates action potentials – electrical impulses – which are then transmitted along the auditory nerve to the brain.

Because different regions of the basilar membrane vibrate maximally for different frequencies, the hair cells in those specific regions are stimulated most effectively. This means that an electrical signal sent to the brain from the basal end of the cochlea will be interpreted as a high-frequency sound, while a signal from the apical end will be perceived as a low-frequency sound. This intricate process transforms the physical energy of sound waves into the neural language of the brain, allowing us to perceive the richness and detail of our auditory environment.

When Things Go Awry: Impact of Basilar Membrane Damage

Given its pivotal role, it's perhaps not surprising that damage to the basilar membrane can have profound consequences for our hearing ability. Its delicate structure, while robust in function, is not impervious to harm.

Common Causes: Noise, Ototoxicity, Age-Related Changes

Several factors can lead to damage or dysfunction of the basilar membrane and the structures it supports:

- Noise Exposure: Prolonged exposure to loud noises, or even short bursts of extremely intense sound, can overstimulate the hair cells and cause excessive vibration of the basilar membrane. This can lead to permanent damage to the hair cells and, in severe cases, the membrane itself. The delicate stereocilia can be broken or fused, and the metabolic machinery of the hair cells can be overwhelmed, leading to their death. This type of damage disproportionately affects the high-frequency region of the basilar membrane (the base), as it is more vulnerable to intense mechanical stress.

- Ototoxicity: Certain medications are known to be ototoxic, meaning they can damage the structures of the inner ear, including the basilar membrane and hair cells. Examples include some antibiotics (e.g., aminoglycosides), chemotherapy drugs, and high doses of aspirin. These substances can interfere with the metabolic processes of the hair cells, leading to their degeneration and subsequent hearing loss.

- Age-Related Hearing Loss (Presbycusis): As we age, the cumulative effects of daily wear and tear, noise exposure, and metabolic changes can lead to a gradual degeneration of the basilar membrane and hair cells. This typically manifests as a progressive, symmetrical hearing loss, often starting with high frequencies, consistent with the vulnerability of the basal end of the membrane.

- Trauma and Disease: Head injuries, infections (like meningitis), or certain autoimmune diseases can also cause inflammation or direct damage to the cochlea, affecting the integrity and function of the basilar membrane.

Consequences: Hearing Loss and Speech Perception Challenges

Damage to the basilar membrane primarily results in sensorineural hearing loss, which is characterized by permanent impairment of sound perception. The specific symptoms depend on the extent and location of the damage:

- Reduced Hearing Sensitivity: If the hair cells are damaged or lost, the ability to convert sound vibrations into electrical signals is diminished, leading to a general reduction in the loudness of perceived sounds.

- Difficulty with Frequency Discrimination: Because the basilar membrane is critical for frequency analysis, damage can disrupt the tonotopic map. This makes it challenging to distinguish between different pitches, which is crucial for appreciating music and, more importantly, understanding speech.

- Speech Perception Difficulties: Speech is a complex acoustic signal, rich in varying frequencies. Damage to the basilar membrane can blur the distinctions between different speech sounds (phonemes), making it incredibly difficult to follow conversations, especially in noisy environments. High-frequency hearing loss, common with basilar membrane damage, makes it hard to hear consonants like "s," "f," "th," and "ch," which carry much of speech's intelligibility.

- Tinnitus: Damage to the basilar membrane or the hair cells it supports can sometimes lead to tinnitus – the perception of ringing, buzzing, or hissing sounds in the absence of an external source. This is often thought to be a result of the brain trying to compensate for the lack of input from damaged regions of the cochlea.

Understanding these consequences underscores the vital importance of protecting our hearing and seeking timely medical attention for any concerns.

Beyond Understanding: Basilar Membrane in Modern Hearing Solutions

The profound understanding of basilar membrane anatomy and function isn't just for academic contemplation; it directly informs the development of cutting-edge solutions for hearing loss, offering hope and practical interventions.

Diagnosis and Treatment Implications

Knowledge of the basilar membrane's mechanics guides audiologists and otolaryngologists in diagnosing the type and degree of hearing loss. Tests like audiograms pinpoint specific frequency ranges where hearing is impaired, often directly correlating to the sections of the basilar membrane that might be compromised. This precise mapping helps in:

- Targeted Hearing Aid Fitting: Modern hearing aids are programmed to amplify specific frequencies that a patient struggles to hear, effectively compensating for the non-functioning or under-functioning parts of the basilar membrane's frequency analysis system.

- Identifying Cochlear vs. Neural Issues: By understanding how the basilar membrane should respond, clinicians can differentiate between damage originating in the cochlea (sensorineural) and problems in the auditory nerve or brain pathways.

Cochlear Implants: Mimicking Nature's Design

Perhaps the most remarkable application of our knowledge about the basilar membrane's tonotopic map is in the development of cochlear implants. For individuals with severe to profound sensorineural hearing loss, where hair cells are extensively damaged and the basilar membrane can no longer effectively transduce sound, cochlear implants offer a revolutionary solution.

A cochlear implant bypasses the damaged hair cells entirely. It consists of an external processor that captures sound and converts it into electrical signals, and an internal array of electrodes surgically implanted directly into the cochlea. These electrodes are strategically placed along the spiral of the cochlea, mimicking the basilar membrane's tonotopic organization.

- High-frequency sounds are directed to electrodes at the base of the cochlea.

- Low-frequency sounds are directed to electrodes at the apex.

By directly stimulating different regions of the auditory nerve fibers in a tonotopically appropriate manner, the cochlear implant effectively "recreates" the place code that the damaged basilar membrane can no longer generate. This allows the brain to receive organized frequency information, enabling users to perceive speech and environmental sounds, and even music, though often with a different quality than natural hearing.

Auditory Rehabilitation and the Tonotopic Map

Beyond technological interventions, the tonotopic map's importance extends to auditory rehabilitation programs. Therapies designed to improve speech perception and sound localization often rely on exercises that retrain the brain to interpret auditory information more effectively, capitalizing on the brain's inherent ability to process tonotopically organized signals. For cochlear implant users, extensive post-implantation therapy helps the brain adapt to the new electrical input, gradually making sense of the tonotopically mapped signals from the device. This process of learning and adaptation underscores the brain's plasticity and its reliance on the ordered frequency information originally provided by the basilar membrane.

Your Ears, Your Health: Protecting Your Basilar Membrane

The basilar membrane is a foundational component of your hearing, an intricate biological marvel that continuously works to translate the world of sound into meaningful information for your brain. Understanding its anatomy and structure reveals not just a complex biological system, but also a profound vulnerability.

Protecting this delicate structure is paramount for lifelong hearing health. This means practicing safe listening habits, like wearing hearing protection in noisy environments, keeping earbud volumes at moderate levels, and taking breaks from sound exposure. It also means being aware of ototoxic medications and discussing potential hearing side effects with your doctor.

Regular hearing check-ups can detect early signs of damage, allowing for intervention and management before issues escalate. The science of hearing, centered on the basilar membrane, continues to evolve, bringing forth new diagnostic tools and therapeutic solutions. By valuing and protecting your hearing, you ensure that this remarkable membrane can continue to perform its vital role, keeping you connected to the sounds of life.